What “Limited Edition” Really Means in the Art World

Copperplate printing press in action, used by masters like Rembrandt to produce finely detailed etchings.

You’ve seen it stamped on concert posters, sneakers, whiskey bottles, perfume bottles, cars—you name it. Limited Edition. It’s everywhere. But in the art world, those two words mean something different. They’re not just marketing copy or an advertising gimmick. They’re part of a centuries-old conversation about value, craftsmanship, and what happens when an artist promises: this will never exist again.

From Copper Plates to Scarcity

The idea traces back to the printmakers. Picture Rembrandt scratching lines into a copper plate. The first impressions—called “pulls”—were razor sharp, every crosshatch crisp, every detail vivid. But the more you printed, the worse the impressions got. By the hundredth print, the plate was already breaking down, the lines blurring like a dull pencil.

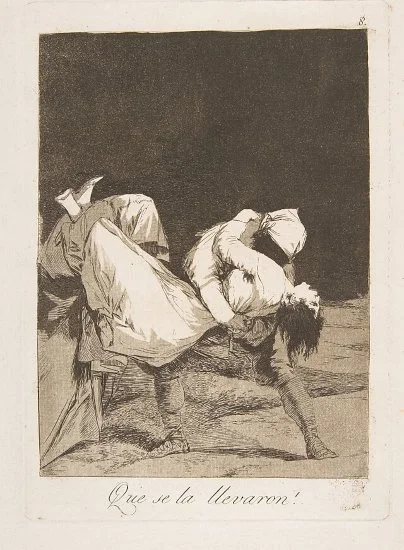

Francisco de Goya, Los Caprichos, Plate 8: “They carried her off!” (1799). Etching, aquatint. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Some artists, like Goya, reworked their plates mid-edition to freshen them. That’s why a first-state print from his Los Caprichos series might sell for six figures, while a later pull from the same plate fetches a fraction. The numbers penciled in the margins—5/100, 10/100—were never just inventory counts. They were a record of the plate’s decay.

“✦ Did You Know?

The word edition comes from the Latin editio, meaning “a bringing forth” or “publication.” Over time it came to mean a particular set of copies released together—like one print run of a book or a series of impressions from a plate. Add the word limited and you get the promise we’re talking about: this set is capped, and once it’s gone, it’s gone.”

By the 1800s, lithographers pushed the idea further. Toulouse-Lautrec personally supervised each pull, signing them by hand and sometimes even destroying the stone afterward. This was the birth of the modern “limited edition”: a fixed number, an artist’s signature, and a tacit promise that no more would follow.

Trust and the Modern Edition

In today’s digital era, the mechanics have changed. Inkjet printers don’t wear down after 50 runs. You could, technically, print a million copies of the same digital file without any visible difference. Which means “limited edition” today isn’t about physical decay—it’s about trust.

When Edward Weston released his famous Pepper No. 30 in the 1930s as a limited edition of 50, he wasn’t worried about plate wear. He was staking a claim: only fifty of these would ever exist, and his signature vouched for each one. Suddenly, photographs—long dismissed as infinitely reproducible—could hold value like a painting.

That’s the paradox of limited editions: they create scarcity where none naturally exists. A painting is one-of-a-kind by default. A print or a photograph? Without that penciled “27/50” in the corner, it’s just another piece of paper.

The Signs of Authenticity

Sharp Art Studio certifcate of authenticity with gold embossed seal.

So how do you know when a limited edition is serious? Look for three things:

Numbering: handwritten, not printed or stickered.

Signature: from the artist’s own hand, not a stamp or auto-pen.

Certification: ideally a certificate of authenticity—or even better, a studio seal embossed directly into the paper.

Some artists add theater to reinforce the pact. Chuck Close famously slashed his plates with a box cutter after the final impression. Julie Mehretu has included DNA samples in her certificates. Dramatic, maybe—but theater matters. In fact, a Sotheby’s study found that signed limited editions by top artists appreciated an average of 8% annually, while open editions barely moved in value.

My Own Commitment to Limited Editions

For me, limited editions are not just a way to make my work available to more people—they’re a way to make sure each piece has weight, dignity, and permanence.

Monti Sharp signing and numbering the 8 × 10 limited edition prints of The Advantage of Being a Ghost.

I’ve never been inspired to buy posters or mass-produced prints at galleries or street fairs, because once I did, I forgot about them. They got lost in a move or tossed out. That is my nightmare as an artist: the idea that my work could feel forgettable or disposable. My process is too deep, too long, and too demanding for me to accept that fate. I want the opposite—I want my work to be cherished, like a photo album you’d never leave behind or a favorite book passed down through generations.

That’s why I insist on the finest papers and inks, on limited runs, and on details like my embossed studio chop—a mark that mystified me when I first encountered it on fine art prints, and one I now proudly press into my own. I number each piece by hand in pencil, sign them in ink, and provide a certificate of authenticity embossed with my gold seal bearing my studio logo. On smaller prints where embossing would intrude on the image, I place my stamp on the back: red for color works, black for black-and-white. Across all of these details is one consistent truth: my collectors can be confident that what they hold is part of a very finite set, made with the same care I devote to an original painting.

I approach this process with the same seriousness I bring to a new canvas. I vet every partner and supplier. I choose archival materials with proven track records. I hold myself to a standard of always learning, always improving, sometimes even at the cost of deadlines, because the best work simply takes the time it takes. That’s the pact I make with collectors: I will only ever give you the best I’m capable of.

The Fragile Pact

Of course, the system isn’t flawless. Throughout history there have been lawsuits filed between parties over secretly recast sculptures or shady practices of overprinting. But when it works, the limited edition system transforms art into a conversation. The collector isn’t just buying an object—they’re buying into a pact between maker and keeper. That pact says: I could have made more, but I didn’t.

And for many of us, that still means something.